Gene Editing with CRISPR/Cas

Digital PCR is an excellent tool for detecting and quantifying genome edits (and their frequency), introduced by CRISPR/Cas, TALEN, and other sequence-editing systems. This is because gene editing-based approaches and therapies (for example, CAR-T cell therapy) typically rely on precise quantification of sometimes very-rare edits, which can monitored without the need for sample purification.

The two most common types of sequence edits introduced by CRISPR/Cas systems are related to the cell’s repair mechanisms following sequence-strand cleavage. NHEJ (Non-Homologous End Joining) is the more common and less specific repair mechanism, often introducing random mutations, including indels of varying lengths. Conversely, HDR (Homology-Directed Repair), with the help of a donor sequence, can introduce specific modifications to the gene of interest (GOI), such as a targeted mutation. Thus, NHEJ is useful for creating gene knockouts, while HDR is valuable for introducing precise, targeted modifications to a GOI.

If working with either NHEJ- or HDR-mediated edits exclusively, I recommend referring to either Drop off probes or the section on Mutation detection (Discrimination assay) in the Basics of Quantification & digital PCR Assay Design. This is because drop-off probes are typically used to detect non-specific mutations (primarily indels) at a target site when working with NHEJ-mediated edits. In contrast, specific single-base edits can be monitored using differently labeled (e.g., FAM/HEX) probes that differ by only one nucleotide. A concise and helpful summary of ddPCR assay design for gene editing can be found in this Bio-Rad bulletin.

If you are investigating both types of repair mechanisms, a combined approach to detect both types of edits may be necessary. Miyaoka et al., 2016 provides a great example of designing gene-editing assays and tracking genome edit frequencies resulting from both NHEJ and HDR repair.

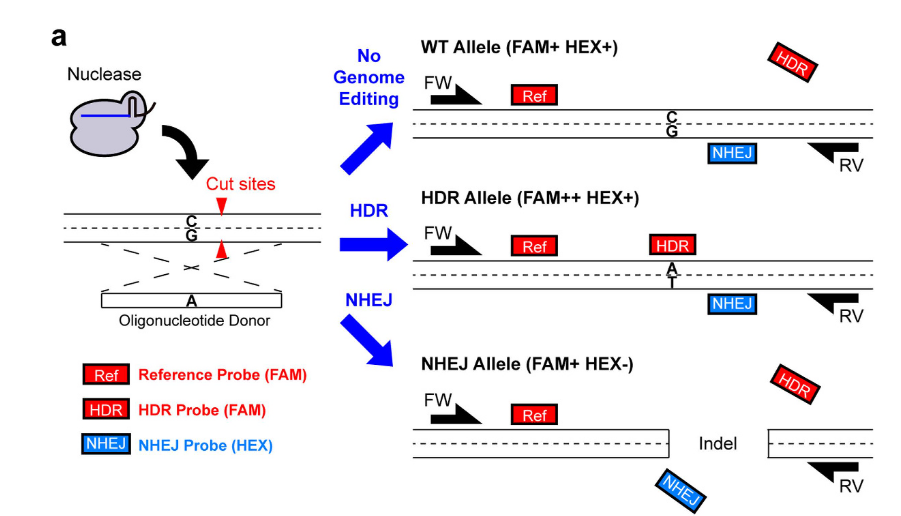

The image below illustrates the approach by Miyaoka et al. In essence:

- No Genome Editing (WT Alleles): Generate a 1x signal for FAM and a 1x signal for HEX.

- HDR Alleles: Produce partitions with a 2x signal intensity for FAM and a 1x signal for HEX. These partitions appear at higher fluorescence amplitude than both No Genome Editing (directly above No Genome Editing, in fact) and NHEJ events.

- NHEJ Alleles: Generate partitions with only a 1x signal intensity for FAM.

source: Miyaoka et al., 2016, Figure 1a

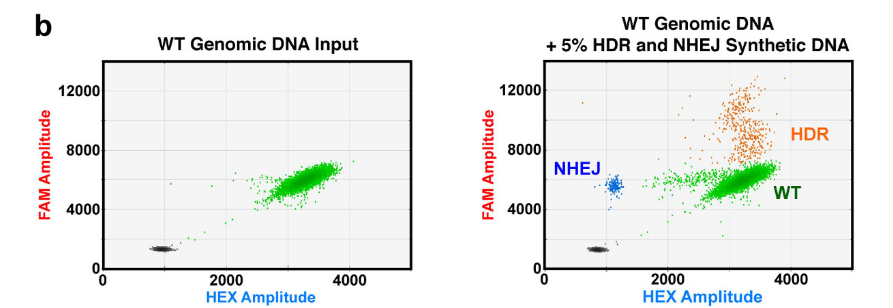

Such a combination of assays can be then successfully utilized to distinguish between unedited DNA, HDR-edited DNA, and NHEJ-edited DNA using only a two-channel system (e.g., QX200, Bio-Rad). Note the contrast (and the appearance of two additional clusters) between the unedited WT Genomic DNA only (left) and the unedited WT Genomic DNA sample, supplemented with an additional 5% HDR and NHEJ Synthethic DNA types (right).

source: Miyaoka et al., 2016, Figure 1 b

In summary, depending on whether you are interested in HDR or NHEJ (or both) mediated edits, assays specific to the different repair types can be easily created, adjusted and run together, using a two-channel-only digital PCR system.

CLEAR-time dPCR

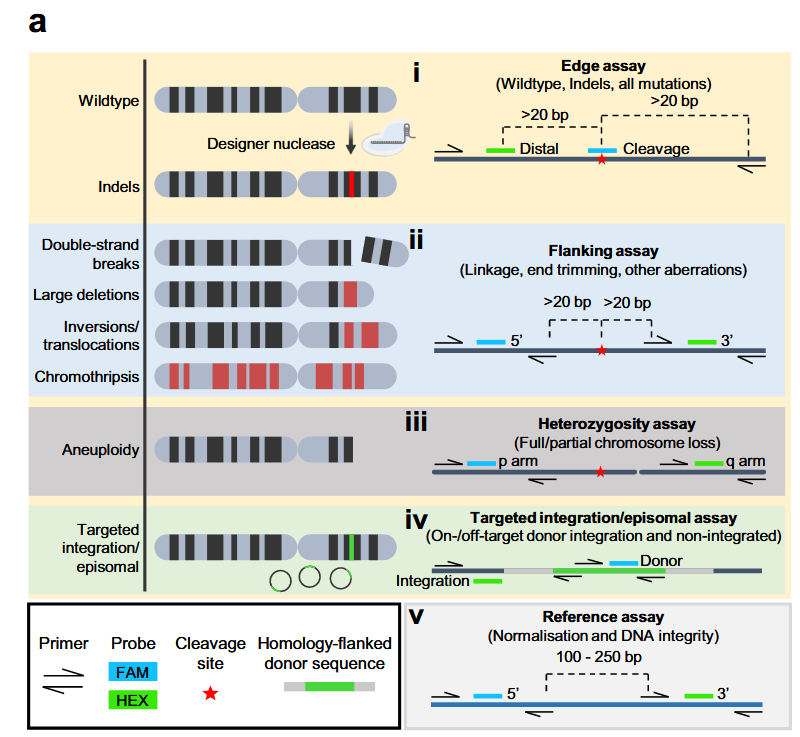

A culmination of detecting and quantifying various mutations, aberrations, DSBs and other effects post gene editing (on a particular locus) with CRIPR/Cas systems is a set of assays (and ultimately a guide) published by White et al., 2025.

Therein, 5 different assays, consisting of a FAM and HEX probe, were used to quantify WT and MT alleles:

source: White et al., 2025, Figure 1 a

The authors compared their 5-assay approach to amplicon sequencing and found that targeted amplicon sequencing tends to overrepresent % of indels when working with mostly intact (very few small indels) sequences. It is of course well known that amplicon sequencing is somewhat biased and preferably amplifies intact sequences while missing longer indels and DSBs.

Most notably, the authors used a double normalization method (each assay copy numbers are normalized against a ref assay (V) and then again against an unedited control sample values). This way, both sample-to-sample variation and between assay variation are accounted for.

Having collected samples at different time points the authors could also tease out the temporal dynamics of editing, increase/decrease of different aberrations as well as the kinetics of different editing/repair strategies by the cells.