Mediator Probe ddPCR

MPddPCR - Mediator Probe droplet digital PCR is a method based off of its qPCR counterpart (the original qPCR method is described here: Lehnert et al., 2018). MPddPCR utilizes a similar approach but has been adapted to be run on digital PCR platforms and is capable of precise and sensitive single nucleotide discrimination (down to 0.009 % variant frequency in some cases) all the while it is claimed to require no cycling or oligonucleotide concentration optimization steps.

The authors that introduced MPddPCR, Schlenker et al., 2021, used this method to investigate common oncologically-relevant mutations (4 KRAS and 1 BRAF SNPs) in clinical samples.

The mechanism of action in MPddPCR

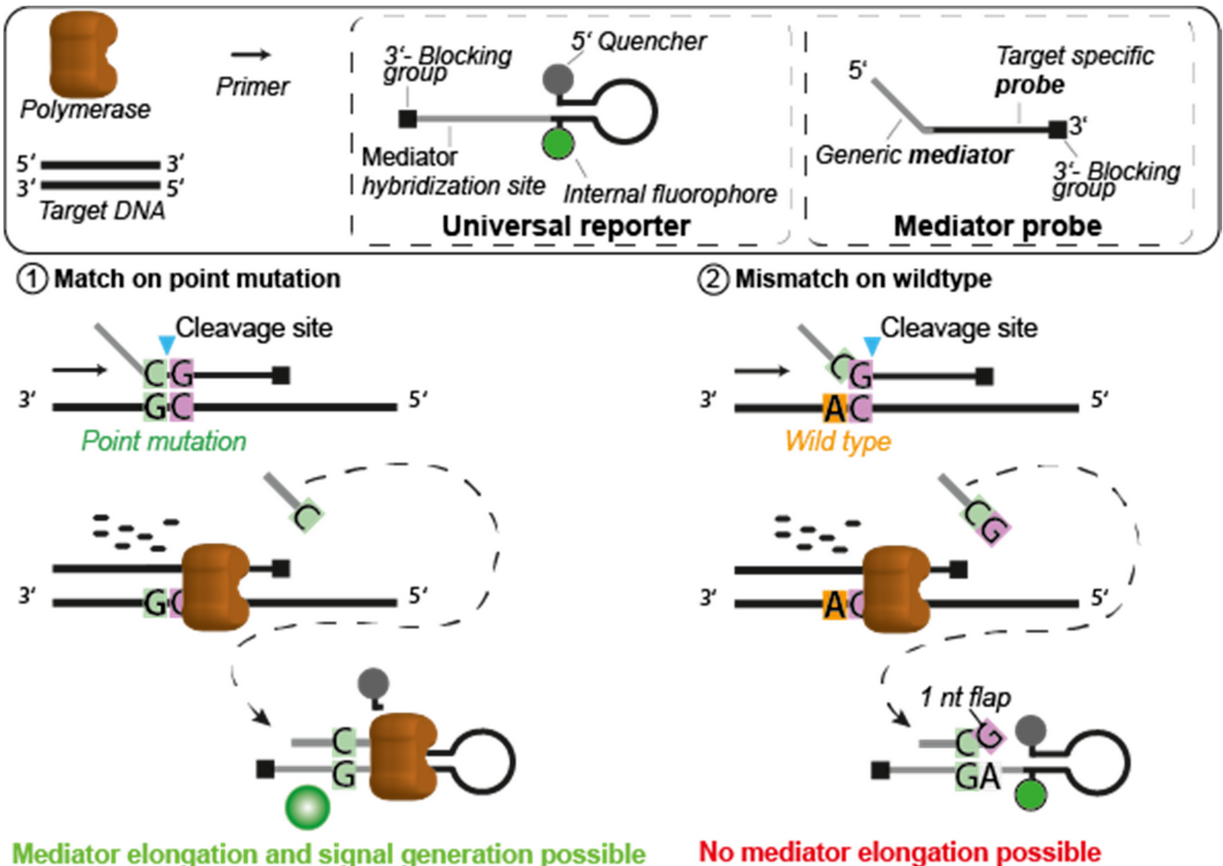

MPddPCR relies on the following components being present in the reaction mix:

- DNA polymerase with 3’→ 5’ endonucleotlytic activity – Cleavage occurs just downstream of the first correctly base-paired nucleotide

- Forward & Reverse primers – Facilitate target locus amplification.

- Universal Reporter – Functions similarly to a molecular beacon; when linearized, it generates a fluorescence signal.

- Mediator Probe – Distinguishes between wild-type (WT) and mutant (MT) sequences by being cleaved at different positions, producing a priming oligo that, when extended, linearizes the Universal Reporter.

During amplification, the Mediator Probe binds at the polymorphic site within the amplicon. Depending on whether the nucleotide is WT or MT, cleavage occurs at different positions. This cleavage generates a free 3’ end, allowing the formation of a short primer that binds to the Universal Reporter. If the polymerase extends this primer, the Universal Reporter is linearized, producing a fluorescence signal.

However, if cleavage occurs even a single nucleotide downstream of the SNP, the resulting one-nucleotide flap prevents polymerase extension when bound to the Universal Reporter. This results in no fluorescence signal.

source: Schlenker et al., 2021, Figure 1

Considerations

Despite the technique being very sensible and intuitive to understand, some key questions about it’s feasibility and applicability in diagnostics remain. Mainly, although the authors state that the technique is optimization-free, they later point out that “transferring this assay to other disease markers, sample types, or readout devices, or to other fluorescence/quencher types, might require a new experimental design”. Some other concerns, relating to data quality (cluster separation and “rain”) are also valid to raise. For example, the supplementary S1 3D plots look very clean, indicating that the template input was likely synthethic DNA. However, further figures S5-S10, showcasing the 1D droplet distribution plots (likely using real samples) have a lot more rain and very little observable separation, indicating that the assays have difficulties with differing efficiency when the input is more complex. This is perhaps not unexpected, given that (similarly to the point i made about MSAddPCR) molecular reactions requiring multiple enzymatic steps are generally less efficient/prone to higher variability in efficiency. Finally, compared to standard TaqMan (hydrolysis) probes, the Mediator Probe system is more intricate, requiring the design of multiple oligonucleotides and potentially limiting its accessibility.

Despite this, MPddPCR represents a novel approach to mutation detection (and thus allele frequency estimation). By utilizing a sequence-specific, polymerase-mediated endonucleolytic cleaving of the Mediator Probe this method enables fluorescence-based SNP detection. If the Mediator Probe binds at a SNP locus, it produces a primer capable of extending the Universal Reporter, generating a fluorescence signal. If bound to a WT locus, no signal is produced.